Japan has an advantage of historically witnessing a stark change from being a traditionally closed country to a modern, international one. That advantage exists because the differences are easier to identify, especially through the lens of sustainability.

During a two-day seminar conducted by the Sustainable Business Japan, they shared that there are three key differences between the Japanese mindset and the Western one: connection with nature versus division of resources, adaptation versus stubbornness, and community versus individualism. This was evident in both business and society.

And it was the Edo period when Japan was a closed economy from the world that laid foundations for what we call a circular economy today. Unfettered by Western mindsets, the Edo period nurtured its reverence for nature and maximized available resources, all without exerting burden on their surroundings for more.

So when Isao Kitabayashi, CEO of COS KYOTO Co., Ltd. and a director of the Sustainable Business Hub Association introduced the term “Circular Edonomy®” at the seminar, we know we were in for a treat. Because we were about to find out how the Edo period evolved to create systems that were sustainable, and formed its own circular economy.

Edonomy®: how the Edo capital’s circular economy looked like

In a way, the circular economy of Edo (the capital of ancient Japan, and the era was thus named after it) is elegant. Multiple industries worked in harmony within the capital, minimizing waste and continued usage the resources within the economy. We will explore more examples, but let’s look at the use of fertilizers in Japan agriculture.

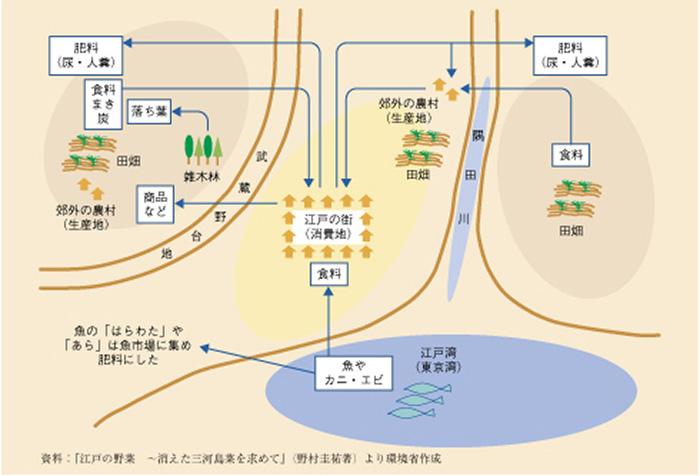

The use of fertilizer is one of the best examples, because of how wide stretching it was used in Edo capital and other nearby towns. As we can see from the image, the central is where the Edo capital is. To the right, lie small villages just outside the capital, and across the river vast spreads of farm land. To the south lies Edo Bay, where fisheries prospered. On the left marks other existing villages and economies in other regions, albeit smaller than Edo capital’s.

From this we will find a circular system without waste. There is consumption, be it the harvest from the fields, or the fish from the ocean. Production of certain goods are exported from the capital to other villages (for example marine produce to villages without access to the ocean). Harvest from the villages returns to the capital for consumption.

The key however is the fertilizers. Bodily waste and scraps from fisheries and fish markets are a valuable resource, as they are collected and sent to the farm fields as fertilizers. What was once consumed from nature gets processed in our body, and is eventually distributed back to nature. Even though the population was about 1 million in the Edo capital, it is still impressive that this circular system was sustainable for Edo and the surrounding villages.

The Edonomy® was also a trading system

One common obstacle circular economies is the lack of certain resources. These resources could be required to start the cycle of production (eg land to grow rice), or already readily available (eg forest for wood). Since the ideal form of such economies does not requiring input of resources and does not output waste, then it might seem impossible.

In our previous example of Edo capital, there is only limited farm land for food. However, it had ready access to the ocean. This became an opportunity for import/export with other villages to make up for missing resources. So we see how the capital and others villages became centers for trade. This allowed these centers to remain sustainable with each other, without taking more from their environment.

How resources were cherished and recycled in the Circular Edonomy®

The fertilizer trade was just one of many examples of how Japan maximised available resources. There are many more examples how resources are reused and recycled, even though words didn’t exist then.

Repairs, instead of discarding as waste

Metal casting

Instead of discarding old or broken cooking pots, there were metal casters whose jobs were to repair them and make them reusable again. These craftsmen utilized a special technique to raise the temperature of charcoal fire. This allowed them to weld another metal plate to cover holes in the metal pots.

Ceramic repair

There were also ceramic craftsmen who were able to use white flour to piece together broken ceramic wares.

Barrel repair

Liquids and condiments were stored in barrels in barrels or baskets, surrounded by bamboo boards tightened together by a wooden ring. Professional craftsmen were called in for repairs whenever these barrels were broken or the rings loosened.

Recycling used resources to reuse

Buying of paper scraps

There were collectors who purchased paper no longer in use, which were in turn recycled. The paper were made from plant fibres that blended easily, making recycling paper scraps effective.

Second-hand clothing

Because the clothing in the Edo period were woven by hand, clothing were valuable. (It is estimated that there were around 4,000 second-hand clothing stores in the Edo capital.)

Buying of old bamboo skeleton

Instead of discarding broken umbrellas, they were sold to collectors. Since the old umbrellas were made through attaching oil paper to bamboo, the paper were carefully peeled off. Both the bamboo skeleton and oil paper were then recycled and reused respectively.

Buying of old barrels

We shared how bamboo barrels that stored liquid and condiments were repaired earlier. When the use of these barrels ended, they were sold to dealers, which is a practice that has endured till today.

Recycling old resources into new life

Buying of candle wax

Candles were considered an item of value during the Edo period. So there were collectors who bought the used, melted wax to recycle them.

Purchasing of fertilizers

We mentioned how bodily wastes were sold to the farmers as fertilizers for their crops. What we didn’t mention was how an infrastructure was built around this business, which was lucrative, handled to prevent disease concerns, and created zero waste.

Buying of firewood ash

The ash leftover from firewood were also considered fertilizers. The households would keep them in a storage till the collectors came by to buy the ash off them.

Instead of starting to be sustainable, Japan should be looking to return to sustainability

Because we live in a modern age of convenience, some of these may bring about questions like, “Why do that to such an extent?” Some may argue that the ancient Japanese had to do these to survive, that it was a necessity, not a choice. However, when we look at the dire state our world is in, how humans are consuming more resources than needed or available, with species going extinct every year and disasters exacerbated by climate change, we no longer have the privilege to call these systems a choice. It is what future generations need.

We have seen how ancient Japan has learned to live in harmony with their environment with their own circular economy. They have shown us that solutions to over consumption already exist. These systems existed well over 200 years of the Edo period, proving how sustainable Circular Edonomy® can be. Surely, if we can adapt the mindset of Edonomy® for the modern period, we can return to when Japan was once sustainable.

More articles about Japan’s circular economy

- 2026-03-12: Circular Economy survery reveals challenges in Japanese companies

- 2026-03-10: Maebashi launches school lunch programme using upcycled vegetables

- 2026-03-10: Itakura Town partners with PASSTO to expand textile resource circulation

- 2026-03-09: Upcycling coconut waste into fire retardant interior tiles

- 2026-03-07: Japanese medical wear sukui wins iF DESIGN AWARD 2026 for circular design